‘Foolhardy failure’

Good morning,

Our meditation today comes from Jared Michelson, Honorary Cornerstone Chaplain. In it he reflects on the “foolhardy failure” of continuing in preaching “as if nothing had happened.” Well, today is a day for foolishness, as it is April Fools’ Day. It’s a day of practical jokes, of pulling the wool over people’s eyes, of falsehoods peddled as truth. My father, who was left-handed, sent me one April Fools’ Day to the local ironmongers for a left-handed screwdriver. There was a funny look in the ironmonger’s eyes when I asked for it. Maybe they were next to the tartan paint and the buckets of steam. Later, I realised my folly, and both my older sisters told me they’d been caught out too in previous years. Have you been fooled yet this morning?

Anyway, here is Jared’s meditation:

In times of crisis and uncertainty, we are inevitably drawn to reflect upon similarly troubled times in the past. During recent weeks, we have often seen analogies drawn between our present circumstances and the dark days which Europe endured during the two world wars. One needs look this far back it seems to locate a time in which society was subjected to as radical a moment of destabilisation. In this light, it may be fitting to look back upon the way in which people of faith responded to such crises to seek resources for our own time.

Four months after Hitler rose to power in Germany, and in response to his attempt to reorganise the church in Germany to make it amenable to the Nazis’ intentions, the Swiss theologian and pastor Karl Barth penned a short tract called Theological Existence To-day! He begins this pamphlet with the seemingly naive and stubborn insistence that theologians, pastors and Christians more broadly, should continue to do theology and preach the gospel as if ‘nothing had happened.’ What might at first glance appear as a foolhardy failure to recognise the uniqueness of his own times and the importance of responding to the present moment, was something else entirely. Barth’s brief tract was destined, in a few short months, to be banned by the Nazi powers. For them, Barth’s tract spoke all too directly to matters of present concern.

Barth’s claim that we should continue speaking about God and practicing faith ‘as if nothing had happened’, is not a call to ignore the significant events taking place around us. It is rather an insistence that the way in which people of faith should respond to a crisis, is not by scraping and striving to find some way in which we might make our faith or holy scriptures appear ‘relevant’ to the present moment. Barth wants us to see that there is no ‘rivalry’ between our religious calling and our vocation to speak about and engage with a present crisis. In fact, if we return to the practices and texts of our faith, or if we attend to the ‘Word of God’ as Barth puts it, we will find that they were always relevant, and in this new light appear only more so. This present moment of uncertainty and doubt serves to present the scriptures and practices of faith in their true light: as speaking intensely, forthrightly, and freshly into the present human condition.

The temptation for some of us might be to think that our spiritual life ‘will no longer be allowed to us… just because we forget to pray and reach out for it.’ Perhaps we feel that prayer or the study of scripture is hopelessly naive, ‘otherworldly,’ and out of place in light of the all-too-worldly crisis which lies before us. Perhaps thinking of God or spiritual concerns simply falls from our minds as we attend to the issues pressing for our attention. Yet among the many things which a powerful political regime or contagious virus cannot take from us—unless we let it—is faith, hope, and love. Attending to the practices of faith is a way of seeking to be formed into the sort of people who can respond to an uncertain situation with faithful trust in the providence of God. These practices shape us as the sorts of persons who refuse to give in to panic, not because the present is not frightening but because God’s goodness gives us grounds for hope. They dispose us to be the sorts of persons who in all things and towards all others respond with patience and love regardless of the circumstances.

Might we, in this sense, carry on as if ‘nothing has happened.’ Yes, we must take all precautions suggested by the government, the NHS, and the University in order to care for one another. Yes, this requires some drastic reordering of our daily lives. Yet in the midst of it all, may we return to a wellspring of faith, hope, and love which remains unchanging.

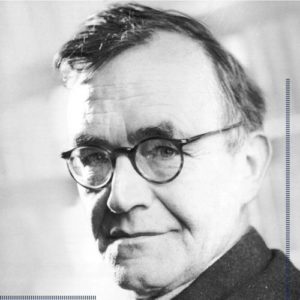

Karl Barth, perhaps around the age he wrote Theological Existence To-day!

Wishing you every blessing for today’s foolishness,

Yours,

Donald.