‘Plague in Eyam’

Good afternoon,

Today’s Companionship message has been contributed by a colleague in the University, who writes as follows about the village of Eyam in Derbyshire, reflecting on a previous outbreak of disease, and selfless actions regarding quarantine:

Something resonated with me about this small village just 5 miles away from where I grew up in Bakewell, Derbyshire. I was about 7 when we first had a school trip there to learn about “the plague” (Black Death) and how it affected these country folk. They behaved selflessly and, in my eyes, heroically. The stones on the outer edges of the village are still there – this was where the “17th century Ocado delivery” would be left. I’ve been to Eyam many times since being 7 years old, and I am always deeply touched and emotional by being there. Walking through the graveyard of the tiny church is so sad, because we know that the dead (apart from one) were not allowed to be buried on this sacred land.

So, here goes with today’s “home schooling” history lesson.

Eyam is a small village in England which lies within the Peak District National Park. At the time of the 2011 census the population was 969.

Eyam is well known as ‘the plague village.’ This is due to the collective act of self-sacrifice the villagers made during an outbreak of the bubonic plague in 1665/1666, when they chose to isolate themselves to prevent the infection spreading to neighbouring villages and the wider community.

The story begins in late August 1665 in a cottage which housed Mary Cooper and her two sons. Mary was a widow who had recently remarried to a man called Alexander Hadfield, a local tailor. A box of cloth from London arrived at the cottage for Mr Hadfield who was away from home at the time. His lodger and rumoured apprentice George Viccars opened the box, and finding the cloth to be damp, he laid it out to dry by the fire.

Soon after George became very ill. It is thought the cloth contained rat fleas which were infected with the bubonic plague. After being bitten by these fleas George died within a week and his funeral took place on 7th September. His burial site is sadly unknown and unmarked. Within a fortnight several more deaths took place. Edward Cooper, Mary’s four year old son was buried on 22nd September and Peter Hawksworth who lived close by was buried on the 23rd. Thomas Thorpe, who also lived in the same row of cottages was buried on the 26th September, followed by his twelve year old daughter Mary on the 30th. Sarah Sydall lived across the road and she also died on the 30th September.

Fear and panic swept through the village, with many people believing they were suffering the wrath of God for being sinful. It is thought that during these early weeks some of the more affluent families may have fled, but there is no record of how many managed to leave. Not many people ventured too far from where they were born and brought up in 1665, and most people were poor and had nowhere to go, nor the means of getting there. The nearest large town was Sheffield and the residents erected barriers and manned guard posts to prevent infected strangers from entering their town. Some of the villagers sought refuge on Eyam Moor or in the fields and caves of Middleton Dale. By the end of October there were 23 more victims who had succumbed to the plague. Amongst them was Jonathon Cooper, Mary Hadfield’s eldest son, another member of the Hawksworth family and five more of the Thorpe family, and a few others. The total of 29 deaths so far had exceeded the average annual mortality rate over the previous decade, although the onset of winter did see a drop in the death rate.

At the end of April 1666 a total of 73 deaths from the plague had been recorded, and at last the villagers thought the worst was over. However these hopes proved to be shortlived as sadly this was only the end of the beginning. By now six of the eight Sydall family members had died and all nine of the Thorpes across the road had perished.

The rector William Mompesson along with his wife Catherine and their two small children were relative newcomers to Eyam. William had begged his wife to take the children to safety, but she refused. Later the children were sent to friends in Yorkshire but Catherine stayed. This selfless act would ultimately cost her her life. Mompesson had noted the sharp increase of deaths in June of 1666, and together with the former rector Thomas Stanley came up with a plan to voice to the villagers of Eyam. At that time it was decided that there would be no more organised funerals and villagers were to bury their own dead in their gardens, fields and orchards. This was not an easy decision, for to their minds not to be buried on consecrated ground meant that their souls would not ascend to Heaven. Burial was to take place as soon as possible after death due to putrefaction releasing the poisonous infection into the atmosphere. The church was also locked down and a collective decision was made to have Sunday services in the open air. No one knew how the disease was spread, and so they came to the conclusion that gathering in confined spaces was something to be avoided. However the most important decision that this small group of people made in the summer of 1666 was to quarantine themselves in Eyam to prevent the outbreak from spreading further afield. By doing so the villagers knew that for many of them all hope was lost and that they were sacrificing themselves to save the lives of others.

Eyam was far from self-sufficient and plans had to be made to provide the quarantined villagers with supplies. The Earl of Devonshire who lived nearby at Chatsworth House proved to be a chief benefactor, and arranged for food and medical supplies to be left at the southern boundary of the village. There was to be no contact between the quarantined and those helping them. Requests and money were left at the boundary stone. Holes were drilled into the stone and the money was left there submerged in vinegar. This was thought to ‘wash the seeds of the plague’ from the coins making them safe to handle. Another place that was used for the exchange of money and goods was what is now known as the Mompesson Well, also on the outskirts of the village. Isolated from the world outside the villagers waited for their fate…

In the next six months the death rate increased dramatically. In June of 1666 there were over 20 deaths, but worse was to come. July saw 56 deaths and the total for August was 78. By now over 200 people had perished in a village of approximately 700. After refusing to leave her husband and working tirelessly to help the sick and dying, Catherine Mompesson was to succumb herself. One of the symptoms of the onset of the disease was the victim speaking of an odd sweet smell. This was in fact the start of the failure and putrefaction of internal organs. One summer evening while walking home with her husband Catherine mentioned the sweet smell of the meadow, and William knew she would die. She is the only Eyam victim to be buried in the churchyard .

It says much for the honour and integrity of this small group of people, that having given their pledge to isolate themselves they kept their word. The suffering of some families was incomprehensible, yet they stayed knowing that their fate was bleak. Jane Hawksworth lost 25 members of her extended family including her husband, her two children, her mother and her brother and his wife. The fate of the Talbot and Hancock families is one of the saddest and most poignant of all. They lived near each other on the hillside overlooking the village about a mile away from the centre of Eyam. They prayed they would be safe but in July 1666 the plague came to the Talbot house. Richard the blacksmith, sisters Bridget and Mary, Anne and Jane and six other family members died before the end of the month. Old Mrs Bridget Talbot, widow of another former rector died on 15th August leaving behind just her great grandchild Catherine, a baby of 3 months old. Catherine subsequently died after allegedly being cared for by the neighbouring Elizabeth Hancock. The first Hancock had died on 3rd August and by the 10th Elizabeth had dragged the bodies of her husband and six of her children up the hillside and buried them herself. It is rumoured that the villagers watched her toil and struggle but daren’t come to her aid for fear of catching the infection. When it was all over Mrs Hancock and her one remaining son left Eyam and settled in Sheffield. The graves of her family are near Riley Wood and can still be seen today, as can the Boundary Stone and Mompesson Well.

Suddenly as Christmas approached it was over, with the last death, that of Abraham Morten being recorded at the beginning of November 1666. He was the 260th person to die. The small village of Eyam in the Derbyshire Dales then quietly took its place in history, as an enduring example of ordinary people making one of the most heroic acts of self-sacrifice in British folklore.

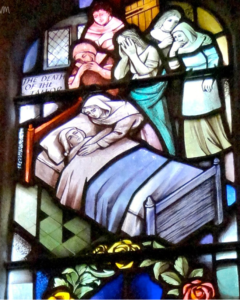

Visitors to St Lawrence’s Church in Eyam can see the plague register copied from the Parish Register of the time, and the stained glass window which tells the story of what happened in Eyam in 14 short months over 350 years ago.

Here’s a photo of one of the boundary stones.

Thank you to that contributor for re-telling that moving story.

Tomorrow, all are welcome to gather remarkably for University worship. St Salvator’s Chapel have newly recorded an audio and video version of the 23rd Psalm set by Walford Davies, the service will be conducted by Sam Ferguson, the Assistant Chaplain, and I will be preaching on The Lord is my Frontline Worker. I will share the order of service tomorrow during the service.

Yours,

Donald.